Pitfall to Avoid: Transfer on Death or Payable on Death not Matching Wills

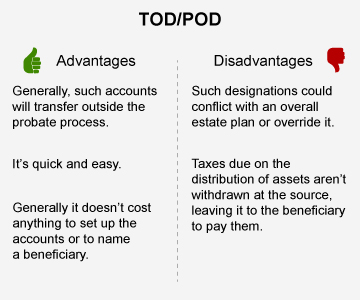

A simple and easy way to help avoid probate is to name someone as a transfer on death (TOD) beneficiary or a payable on death (POD) beneficiary.

The terms are essentially the same but apply to slightly different accounts. A TOD/POD beneficiary can be named on financial accounts, such as bank savings or checking accounts and investment accounts, vehicle titles, and––in some states––real property.

The terms are essentially the same but apply to slightly different accounts. A TOD/POD beneficiary can be named on financial accounts, such as bank savings or checking accounts and investment accounts, vehicle titles, and––in some states––real property.

Despite their simplicity, one major issue with TOD/POD-titled assets is a lack of awareness or poor coordination with people’s overall estate planning strategies.

If a number of accounts are titled as TOD, a will can be rendered largely ineffective, and assets may not be distributed as intended.

“You could have a complex will with all sorts of trusts created for your children,” says Pamela Pirone-Benson, a Fidelity estate planning specialist. “But if the assets don’t pass by the terms of the will, then the will becomes an expensive paperweight.”

Lubar describes transfer on death as a “placeholder,” rather than an estate plan. “It’s a temporary bandage until you put a larger, more effective, comprehensive plan in place.”

Consider Susan, a hypothetical client with a brokerage account worth $1 million.

She names her husband as a TOD beneficiary of the $1 million account. Five years later, she does some estate planning and states in her will that the account’s assets be split evenly between her two daughters from a different marriage.

Unfortunately, Susan doesn’t realize that her now ex-husband will receive the assets, because the TOD registration overrides the will.

Another problem with a TOD or POD could occur if parents name their children individually as TOD on each of two separate accounts. At the time the assets are titled, the value of the two accounts is equal. But no one tracks the value of the accounts over time.

Thirty years later, when the couple dies, one child could receive a much smaller sum than the other.

She names her husband as a TOD beneficiary of the $1 million account. Five years later, she does some estate planning and states in her will that the account’s assets be split evenly between her two daughters from a different marriage.

Unfortunately, Susan doesn’t realize that her now ex-husband will receive the assets, because the TOD registration overrides the will.

Another problem with a TOD or POD could occur if parents name their children individually as TOD on each of two separate accounts. At the time the assets are titled, the value of the two accounts is equal. But no one tracks the value of the accounts over time.

Thirty years later, when the couple dies, one child could receive a much smaller sum than the other.

And estate taxes may be due on TOD assets and payable by the recipient, depending on, among other things, how the will is drafted.

“This can create an administrative nightmare for the executor of the will, who then needs to go and collect taxes from the recipients after they receive the assets,” says Pirone-Benson.

“This can create an administrative nightmare for the executor of the will, who then needs to go and collect taxes from the recipients after they receive the assets,” says Pirone-Benson.